How many are there?

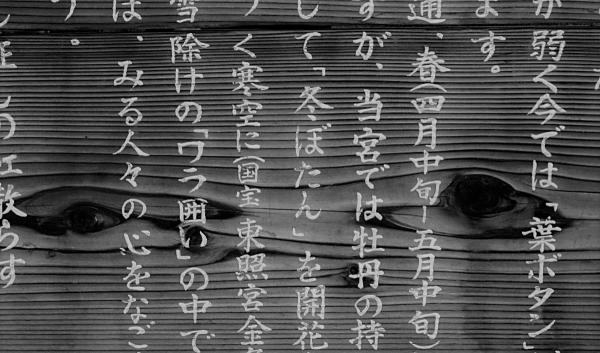

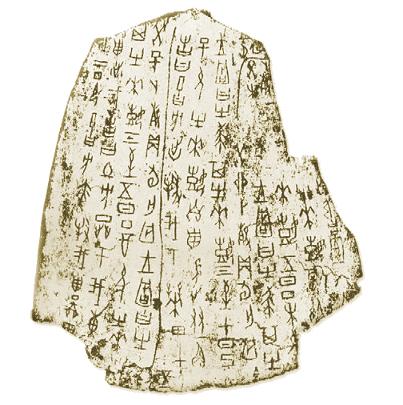

It is difficult to answer this question since there is no exact number. Adoption of characters from China was a long and complicated process and some characters were altered or simplified along the way. Moreover, there are some characters of Japanese origin that do not exist in Chinese. Furthermore, the total number of the adopted original Chinese characters is unknown. But there are thousands of kanji.

Of course, learning thousands of kanji would be too much even for the Japanese. Most of them are not even used actively. That is why there is an official list of commonly used kanji which are called jōyō kanji (常用漢字). The list has 2,136 characters as of now. The Japanese have to learn these over the years of their compulsary education, so that they can read newspapers, books etc. Actually, reasonably educated Japanese people usually know more kanji (at least passively) and thus we can find characters that are not on the jōyō kanji list in literature and other texts.

Apart from the jōyō kanji, there are other categories of characters. One of them is a group of kanji used to write first and last names of people, the so-called jinmeiyō kanji (人名用漢字). If we add up jōyō kanji and jinmeiyō kanji, we get 2,998 characters.